A Step by Step Guide¶

This step by step guide goes through the whole process of designing and testing a domain specific notation with the DHParser-package from the very start. (The terms “domain specific notation” and “domain specific language” are used interchangeably in the following. Both will be abbreviated by “DSL”, however.) We will design a simple domain specific notation for poems as a teaching example. On the way we will learn:

how to setup a new DHParser project

how to use the test driven development approach to designing a DSL

how to describe the syntax of a DSL with the EBNF-notation

how to specify the transformations for converting the concrete syntax tree that results from parsing a text denoted in our DLS into an abstract syntax tree that represents or comes close to representing our data model.

how to write a compiler that transforms the abstract syntax tree into a target representation which might be a html page, epub or printable pdf in the case of typical Digital-Humanities-projects.

System-Requirements¶

DHParser runs on Linux, MacOS and Windows. The following step by step

guide assumes that you already have a Python-interpreter installed on

your system and added the python-command to your PATH-variable. (The

latter is usually done automatically when installing Python.)

Furthermore, DHParser only works with Python Version 3.5.3 and above. In

order to verify this, open a shell or command line and type:

$ python --version

Python 3.7.7

If Python plus a version number greater or equal 3.7 does not appear, you’ll

need to install Python from python.org.

Setting up a new DHParser project¶

Since DHParser, while quite mature in terms of implemented features, is still in a pre-first-release state, it is, for the time being, more recommendable to clone the most current version of DHParser from the git-repository rather than installing the packages from the Python Package Index (PyPI).

This section takes you from cloning the DHParser git repository to setting up

a new DHParser-project in the experimental-subdirectory and testing

whether the setup works. Similarly to current web development practices, most

of the work with DHParser is done from the shell. In the following, we assume

a Unix (Linux) environment. The same can most likely be done on other

operating systems in a very similar way, but there might be subtle

differences.

Installing DHParser from the git repository¶

In order to install DHParser from the git repository, open up a shell window and type:

$ git clone https://gitlab.lrz.de/badw-it/DHParser.git

$ cd DHParser

The second command changes to the DHParser directory. Within this directory you should recognize the following subdirectories and files. There are more files and directories for sure, but those will not concern us for now:

DHParser/ - the DHParser python packages

DHParser/scripts - contains the command line tool "dhparser.py"

documentation/ - DHParser's documentation in html-form

documentation_src - DHParser's documentation in reStructuredText-Format

examples/ - some examples for DHParser (mostly incomplete)

experimental/ - an empty directory for experimenting

test/ - DHParser's unit-tests

README.md - General information about DHParser

LICENSE.txt - DHParser's license. It's open source (hooray!)

Introduction.md - An introduction and appetizer for DHParser

In order to verify that the installation works, you can run the

dhparser.py-script and, when asked, chose “3” for the self-test:

$ python DHParser/scripts/dhparser.py

Usage:

dhparser.py PROJECTNAME - to create a new project

dhparser.py FILENAME.ebnf - to produce a python-parser from an EBNF-grammar

dhparser.py --selftest - to run a self-test

Would you now like to ...

[1] create a new project

[2] compile an ebnf-grammar

[3] run a self-test

[q] to quit

Please chose 1, 2 or 3> 3

DHParser selftest...

If the self-test runs through without error, the installation has succeeded.

Note

On Microsoft Windows Systems you’ll have to use the backslash \

instead of the forward slash / as a delimiter for file paths. Thus,

if you are not working on MacOS oder Linux (which I recommend), you’ll

have to type python DHParser\scripts\dhparser.py on the command line

(“Eingabeaufforderung”) to run the script.

Starting a new DHParser project¶

In order to setup a new DHParser project, you run the dhparser.py-script

with the name of the new project. For the sake of the example, let’s type:

$ python DHParser/scripts/dhparser.py experimental/poetry

$ cd experimental/poetry

This creates a new DHParser-project with the name “poetry” in directory with the same name within the subdirectory “experimental”. This new directory contains the following files:

README.md - a stub for a readme-file explaining the project

poetry.ebnf - a trivial demo grammar for the new project

example.dsl - an example file written in this grammar

tst_poetry_grammar.py - a python script ("test-script") that re-compiles

the grammar (if necessary) and runs the unit tests

poetryServer.py - a script that starts the poetry parser as a server

which can save startup time among other benefits

tests_grammar/01_test_Regular_Expressions.ini - a demo unit test

tests_grammar/02_test_Structure_and_Components.ini - another unit test

Now, if you look into the file “example.dsl” you will find that it contains a simple sequence of words, namely “Life is but a walking shadow”. In fact, the demo grammar that comes with a newly created project is nothing but simple grammar for sequences of words separated by whitespace. Now, since we already have unit tests, our first exercise will be to run the unit tests by starting the script “tst_poetry_grammar.py”:

$ python tst_poetry_grammar.py

This will run through the unit-tests in the grammar_tests directory and print their success or failure on the screen. If you check the contents of your project directory after running the script, you might notice that there now exists a new file “poetryParser.py” in the project directory. This is an auto-generated compiler-script for our DSL. You can use this script to compile any source file of your DSL, like “example.dsl”. Let’s try:

$ python poetryParser.py --xml example.dsl

The output is a block of pseudo-XML, looking like this:

<document>

<WORD>

<ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>Life</ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>

<ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__> </ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__>

</WORD>

<WORD>

<ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>is</ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>

<ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__> </ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__>

</WORD>

...

Now, this does not look too helpful yet. However, you might notice that it contains the original sequence of words “Life is but a walking shadow” in a structured form, where each word is (among other things) surrounded by <WORD>-tags. In fact, the output of the compiler script is a pseudo-XML-representation of the concrete syntax tree of our “example.dsl”-document according the grammar specified in “poetry.ebnf” (which we haven’t looked into yet, but we will do so soon).

If you see the pseudo-XML on screen, the setup of the new DHParser-project has been successful.

Developing a DHParser-project¶

Understanding how compilation of DSL-documents with DHParser works¶

Generally speaking, the compilation process consists of three stages:

Parsing a document. This yields a concrete syntax tree (CST) of the document.

Transforming. This transforms the CST into the much more concise abstract syntax tree (AST) of the document.

Compiling. This turns the AST into anything you’d like, for example, an XML-representation or a relational database record.

Now, DHParser can fully automatize the generation of a parser from a syntax-description in EBNF-form, like our “poetry.ebnf”, but it cannot automatize the transformation from the concrete into the abstract syntax tree (which for the sake of brevity we will simply call “AST-Transformation” in the following), and neither can it automatize the compilation of the abstract syntax tree into something more useful. Therefore, the AST-Transformation in the autogenerated compile-script is simply left empty, while the compiling stage simply converts the syntax tree into a pseudo-XML-format.

The latter two stages have to be coded into the compile-script by hand, with the support of templates within this script. If the grammar of the DSL is changed - as it will be frequently during the development of a DSL - the parser-part of this script will be regenerated by the testing-script before the unit tests are run. The script will notice if the grammar has changed. This also means that the parser part of this script will be overwritten and should never be edited by hand. The other two stages can and should be edited by hand. Stubs for theses parts of the compile-script will only be generated if the compile-script does not yet exist, that is, on the very first calling of the test-script.

Usually, if you have adjusted the grammar, you will want to run the unit tests anyway. Therefore, the regeneration of the parser-part of the compile-script is triggered by the test-script.

The development workflow for DSLs¶

When developing a domain specific notation it is recommendable to first develop the grammar and the parser for that notation, then to the abstract syntax tree transformations and finally to implement the compiler. Of course one can always come back and change the grammar later. But in order to avoid revising the AST-transformations and the compiler time and again it helps if the grammar has been worked out before. A bit of interlocking between these steps does not hurt, though.

A reasonable workflow for developing the grammar proceeds like this:

Set out by writing down a few example documents for your DSL. It is advisable to start with a few simple examples that use only a subset of the intended features of your DSL.

Next you sketch a grammar for your DSL that is just rich enough to capture those examples.

Right after sketching the grammar you should write test cases for your grammar. The test cases can be small parts or snippets of your example documents. You could also use your example documents as test cases, but usually the test cases should have a smaller granularity to make locating errors easier.

Next, you should run the test script. Usually, some test will fail at the first attempt. So you’ll keep revising the EBNF-grammar, adjusting and adding test cases until all tests pass.

Now it is time to try and compile the example documents. By this time the test-script should have generated the compile-script, which you can be called with the example documents. Don’t worry too much about the output, yet. What is important at this stage is merely whether the parser can handle the examples or not. If not, further test cases and adjustments the EBNF grammar will be needed - or revision of the examples in case you decide to use different syntactic constructs.

If all examples can be parsed, you go back to step one and add further more complex examples, and continue to do so until you have the feeling that your DSL’s grammar is rich enough for all intended application cases.

Let’s try this with the trivial demo example that comes with creating a new project with the “dhparser.py”-script. Now, you have already seen that the “example.dsl”-document merely contains a simple sequence of words: “Life is but a walking shadow” Now, wouldn’t it be nice, if we could end this sequence with a full stop to turn it into a proper sentence. So, open “examples.dsl” with a text editor and add a full stop:

Life is but a walking shadow.

Now, try to compile “examples.dsl” with the compile-script:

$ python poetryParser.py example.dsl

example.dsl:1:29: Error (1010): EOF expected, ».\n ...« found!

example.dsl:1:29: Error (1040): Parser stopped before end! Terminating parser.

Since the grammar, obviously, did not allow full stops so far, the parser returns an error message. The error message is pretty self-explanatory in this case. (Often, you will unfortunately find that the error message are somewhat difficult to decipher. In particular, because it so happens that an error the parser complains about is just the consequence of an error made at an earlier location that the parser may not have been able to recognize as such. We will learn more about how to avoid such situations, later.) EOF is actually the name of a parser that captures the end of the file, thus “EOF”! But instead of the expected end of file an, as of now, unparsable construct, namely a full stop followed by a line feed, signified by “n”, was found.

Let’s have look into the grammar description “poetry.ebnf”. We ignore the beginning of the file, in particular all lines starting with “@” as these lines do not represent any grammar rules, but meta rules or so-called “directives” that determine some general characteristics of the grammar, such as whitespace-handling or whether the parser is going to be case-sensitive. Now, there are exactly three rules that make up this grammar:

document = ~ { WORD } §EOF

WORD = /\w+/~

EOF = !/./

EBNF-Grammars describe the structure of a domain specific notation in top-down fashion. Thus, the first rule in the grammar describes the components out of which a text or document in the domain specific notation is composed as a whole. The following rules then break down the components into even smaller components until, finally, there a only atomic components left which are described be matching rules. Matching rules are rules that do not refer to other rules any more. They consist of string literals or regular expressions that “capture” the sequences of characters which form the atomic components of our DSL. Rules in general always consist of a symbol on the left hand side of a “=”-sign (which in this context can be understood as a definition signifier) and the definition of the rule on the right hand side.

Note

Traditional parser technology for context-free grammars often distinguishes two phases, scanning and parsing, where a lexical scanner would take a stream of characters and yield a sequence of tokens and the actual parser would then operate on the stream of tokens. DHParser, however, is an instance of a scanner-less parser where the functionality of the lexical scanner is seamlessly integrated into the parser. This is done by allowing regular expressions in the definiendum of grammar symbols. The regular expressions do the work of the lexical scanner.

Theoretically, one could do without scanners or regular expressions. Because regular languages are a subset of context-free languages, parsers for context-free languages can do all the work that regular expressions can do. But it makes things easier - and, in the case of DHParser, also faster - to use them.

In our case the text as a whole, conveniently named “document” (any other name would be allowed, too), consists of a leading whitespace, a possibly empty sequence of an arbitrary number of words words ending only if the end of file has been reached. Whitespace or, more precisely, insignificant whitespace in DHParser-grammars is always denoted by a tilde “~”. Thus, the definiens of the rule “document” starts with a “~” on the right hand side of the definition sign (“=”). Next, you find the symbol “WORD” enclosed in braces. “WORD”, like any symbol composed of letters in DHParser, refers to another rule further below that defines what words are. The meaning of the braces is that whatever is enclosed by braces may be repeated zero or more times. Thus the expression “{ WORD }” describes a sequence of arbitrarily many repetitions of WORD, whatever WORD may be. Finally, EOF refers to yet another rule defined further below. We do not yet know what EOF is, but we know that when the sequence of words ends, it must be followed by an EOF. The paragraph sign “§” in front of EOF means that it is absolutely mandatory that the sequence of WORDs is followed by an EOF. If it doesn’t the program issues an error message. Without the “§”-sign the parser simply would not match, which in itself is not considered an error.

Note

Often when parsing or transforming texts, there is a distinction between significant whitespace and insignificant whitespace. For example, whitespace at the beginning of a text could be considered insignificant, because the text does not change when the whitespace at the beginning is removed. By the same token, whitespace between words could be considered as significant. It is, however, a matter of convention and purpose, when and whether whitespace is to be considered insignificant. For example, a typesetter might not quite agree that whitespace at the beginning of a text is insignificant. And in our example, whitespace between words is considered as semantically insignificant, because – even though it is needed during the parsing process – we know by definition that words must be separated by whitespace, so that we can safely leave it out of our data model (see below). In fact, all whitespace in our example is thus considered as insignificant.

If, however, the distinction is made between a significant and an

insignificant type of whitespace – which is often reasonable, then the

insignificant whitespace should be denoted by DHParser’s default sign for

whitespace, that is a tilde “~”, while significant whitespace should be

explicitly defined in the grammar, for example by introducing a

definition like S = /\s+/ into the grammar.

Here is a little exercise: Can you rewrite the grammar of this example so as to distinguish between significant whitespace between words and insignificant whitespace at the beginning of the text? Why could it be useful to keep whitespace in the data model, even if the presence of whitespace follows strict conventions (e.g. between any two consecutive words there must be whitespace and at the beginning of the second and all following paragraphs there is to be whitespace and the like)? Discuss.

Now, let’s look at our two matching rules. Both of these rules contain regular

expressions. If you do not know about regular expressions yet, you should head

over to an explanation or tutorial on

regular expressions

before continuing, because we are

not going to discuss them here. In DHParser-Grammars regular expressions are

enclosed by simple forward slashes “/”. Everything between two forward slashes

is a regular expression as it would be understood by Python’s “re”-module.

Thus the rule WORD = /\w+/~ means that a word consists of a sequence of

letters, numbers or underscores ‘_’ that must be at least one sign long. This

is what the regular expression “w+” inside the slashes means. In regular

expressions, “w” stands for word-characters and “+” means that the previous

character can be repeated one or more times. The tile “~” following the

regular expression, we already know. It means that a a word can be followed by

whitespace. Strictly speaking that whitespace is part of “WORD” as it is

defined here.

Similarly, the EOF (for “end of line”) symbol is defined by a rule that consists of a simple regular expression, namely “.”. The dot in regular expressions means any character. However, the regular expression itself preceded by an exclamations mark “!”. IN DHParser-Grammars, the explanation mark means “not”. Therefore the whole rule means, that no character must follow. Since this is true only for the end of file, the parser looking for EOF will only match if the very end of the file has been reached.

Now, what would be the easiest way to allow our sequence of words to be ended like a real sentence with a dot “.”? As always when defining grammars one can think of different choices to implement this requirement in our grammar. One possible solution is to add a dot-literal before the “§EOF”-component at the end of the definition of the “document”-rule. So let’s do that. Change the line where the “document”-rule is defined to:

document = ~ { WORD } "." §EOF

As you can see, string-literals are simply denoted as strings between inverted commas in DHParser’s variant of the EBNF-Grammar. Now, before we can compile the file “example.dsl”, we will have to regenerate our parser, because we have changed the grammar. In order to recompile, we simply run the test-script again:

$ python tst_poetry_grammar.py

But what is that? A whole lot of error messages? Well, this it not surprising, because we change the grammar, some of our old test-cases fail with the new grammar. So we will have to update our test-cases. Actually, the grammar gets compiled never the less and we could just ignore the test failures and carry on with compiling our “example.dsl”-file again. But, for this time, we’ll follow good practice and adjust the test cases. So open the test that failed, “grammar_tests/02_test_Structure_and_Components.ini”, in the editor and add full stops at the end of the “match”-cases and remove the full stop at the end of the “fail”-case:

[match:document]

M1: """This is a sequence of words

extending over several lines."""

M2: """ This sequence contains leading whitespace."""

[fail:document]

F1: """This test should fail, because neither

comma nor full stop have been defined anywhere"""

The format of the test-files should be pretty self-explanatory. It is a simple ini-file, where the section markers hold the name of the grammar-rule to be tested which is either preceded by “match” or “fail”. “match” means that the following examples should be matched by the grammar-rule. “fail” means they should not match. It is just as important that a parser (or grammar-rules) does not match those strings it should not match as it is that it matches those strings that it should match. The individual test-cases all get a name, in this case M1, M2, F1, but if you prefer more meaningful names this is also possible. (Beware, however, that the names for the match-tests must be different from the names for the fail-tests for the same rule!). Now, run the test-script again and you’ll see that no errors get reported any more.

Finally, we can recompile out “example.dsl”-file, and by its XML output we can tell that it worked:

$ python poetryParser.py --xml example.dsl

So far, we have seen in nuce how the development workflow for building up a DSL-grammar goes. Let’s take this a step further by adding more capabilities to our grammar.

Extending the example DSL further¶

A grammar that can only digest single sentences is certainly rather boring. So we’ll extend our grammar a little further so that it can capture paragraphs of sentences. To see, where we are heading, let’s first start a new example file, let’s call it “macbeth.dsl” and enter the following lines:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour

upon the stage and then is heard no more. It is a tale told by an idiot,

full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

What have we got, there? We’ve got a paragraph that consists of several sentences each of which ends with a full stop. The sentences themselves can consist of different parts which are separated by a comma. If, so far, we have got a clear idea (in verbal terms) of the structure of texts in our DSL, we can now try to formulate this in the grammar.:

document = ~ { sentence } §EOF

sentence = part {"," part } "."

part = { WORD } # a subtle mistake, right here!

WORD = /\w+/~ # something forgotten, here!

EOF = !/./

The most important new part is the grammar rule “sentence”. It reads as this: A sentence is a part of a sentence potentially followed by a repeated sequence of a comma and another part of a sentence and ultimately ending with a full stop. (Understandable? If you have ever read Russell’s “Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy” you will be used to this kind of prose. Other than that I find the formal definition easier to understand. However, for learning EBNF or any other formalism, it helps in the beginning to translate the meaning of its statements into plain language.)

There are two subtle mistakes in this grammar. If you can figure them out

just by thinking about it, feel free to correct the grammar right now. (Would

you really have noticed the mistakes if they hadn’t already been marked in the

code above?) For all less intelligent people, like me: Let’s be prudent and -

since the grammar has become more complex - add a few test cases. This should

make it easier to locate any errors. So open up an editor with a new file in

the tests subdirectory, say grammar_tests/03_test_sentence.ini (Test files

should always contain the component test_ in the filename, otherwise they

will be overlooked by DHParser’s unit testing subsystem) and enter a few

test-cases like these:

[match:sentence]

M1: """It is a tale told by an idiot,

full of sound and fury, signifying nothing."""

M2: """Plain old sentence."""

[fail:sentence]

F1: """Ups, a full stop is missing"""

F2: """No commas at the end,."""

Again, we recompile the grammar and run the test at the same time by running the testing-script:

$ python tst_poetry_grammar.py

...

Errors found by unit test "03_test_sentence.ini":

Fail test "F2" for parser "sentence" yields match instead of expected failure!

Too bad, something went wrong here. But what? Didn’t the definition of the rule “sentence” make sure that parts of sentences are, if at all, only be followed by a sequence of a comma and another part of a sentence. So, how come that between the last comma and the full stop there is nothing but empty space? Ah, there’s the rub! If we look into our grammar, how parts of sentences have been defined, we find that the rule:

part = { WORD }

defines a part of a sentence as a sequence of zero or more WORDs. This means that a string of length zero also counts as a valid part of a sentence. Now in order to avoid this, we could write:

part = WORD { WORD }

This definition makes sure that there is at least on WORD in a part. Since the case that at least one item is needed occurs rather frequently in grammars, DHParser offers a special syntax for this case:

part = { WORD }+

(The plus sign “+” must always follow directly after the curly brace “}”

without any whitespace in between, otherwise DHParser won’t understand it.)

At this point the worry may arise that the same problem could reoccur at

another level, if the rule for WORD would match empty strings as well. Let’s

quickly add a test case for this to the file

grammar_tests/01_test_Regular_Expressions.ini:

[fail:WORD]

F1: two words

F2: ""

Thus, we are sure to be warned in case the definition of rule “WORD” matches the empty string. Luckily, it does not do so now. But it might happen that we change this definition later again for some reason, we might have forgotten about this subtlety and introduce the same error again. With a test case we can reduce the risk of such a regression error. This time the tests run through, nicely. So let’s try the parser on our new example:

$ python poetryParser.py macbeth.dsl

macbeth.dsl:1:1: Error (1010): EOF expected; "Life’s but" found!

macbeth.dsl:1:1: Error (1040): Parser stopped before end! Terminating parser.

That is strange. Obviously, there is an error right at the beginning (line 1 column 1). But what could possibly be wrong with the word “Life”. Now you might already have guessed what the error is and that the error is not exactly located in the first column of the first line.

Unfortunately, DHParser - like almost any other parser out there - is not always very good at spotting the exact location of an error. Because rules refer to other rules, a rule may fail to parse - or, what is just as bad, succeed to parse when it should indeed fail - as a consequence of an error in the definition of one of the rules it refers to. But this means if the rule for the whole document fails to match, the actual error can be located anywhere in the document! There a different approaches to dealing with this problem. A tool that DHParser offers is to write log-files that document the parsing history. The log-files allow to spot the location, where the parsing error occurred. However, you will have to look for the error manually. A good starting point is usually either the end of the parsing process or the point where the parser reached the farthest into the text. In order to receive the parsing history, you need to run the compiler-script again with the debugging option:

$ python poetryParser.py --debug macbeth.dsl

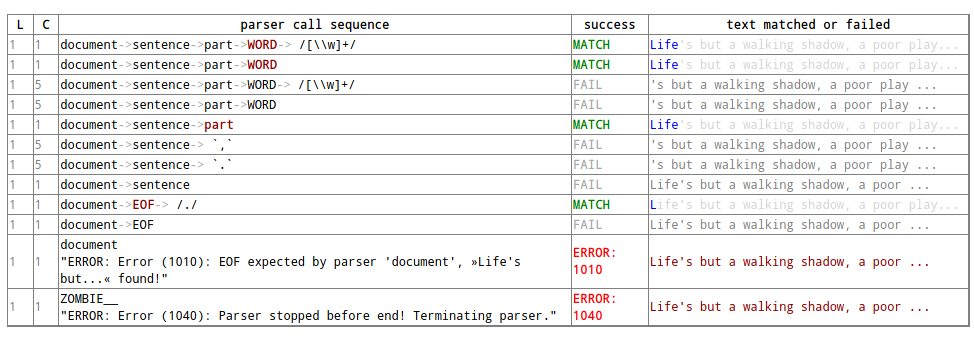

You will receive the same error messages as before. but this time various kinds of debugging information have been written into a newly created subdirectory “LOGS”. (Beware that any files in the “LOGS” directory may be overwritten or deleted by any of the DHParser scripts upon the next run! So don’t store any important data there.) The most interesting file in the “LOGS”-directory is the full parser log. We’ll ignore the other files and just open the file “macbeth_full_parser.log.html” in an internet-browser. As the parsing history tends to become quite long, this usually takes a while, but luckily not in the case of our short demo example:

$ firefox LOGS/macbeth_full_parser.log.html &

What you see is a representation of the parsing history. It might look a bit tedious in the beginning, especially the column that contains the parser call sequence. But it is all very straight forward: For every application of a match rule, there is a row in the table. Typically, match rules are applied at the end of a long sequence of parser calls that is displayed in the third column. You will recognize the parsers that represent rules by their names, e.g. “document”, “sentence” etc. Those parsers that merely represent constructs of the EBNF grammar within a rule do not have a name and are represented by this type, which always begins with a colon, like “:ZeroOrMore”. Finally, the regular expression or literal parsers are represented by the regular expression pattern or the string literal themselves. (Arguably, it can be confusing that parsers are represented in three different ways in the parer call sequence. I am still figuring out a better way to display the parser call sequence. Any suggestions welcome!) The first two columns display the position in the text in terms of lines and columns. The second but last column, labeled “success” shows whether the last parser in the sequence matched or failed or produced an error. In case of an error, the error message is displayed in the third column as well. In case the parser matched, the last column displays exactly that section of the text that the parser did match. If the parser did not match, the last column displays the text that still lies ahead and has not yet been parsed.

In our concrete example, we can see that the parser “WORD” matches

“Life”, but not “Life’s” or “’s”. And this ultimately leads to the

failure of the parsing process as a whole. The most simple solution

would be to add the apostrophe to the list of allowed characters in a

word by changing the respective line in the grammar definition to WORD

= /[\w’]+/~. Now, before we even change the grammar we first add

another test case to capture this kind of error. Since we have decided

that “Life’s” should be parsed as a singe word, let’s open the file

“grammar_tests/01_test_Regular_Expressions.ini” and add the following

test:

[match:WORD]

M3: Life’s

To be sure that the new test captures the error we have found you might want to run the script “tst_poetry_grammar.py” and verify that it reports the failure of test “M3” in the suite “01_test_Regular_Expressions.ini”. After that, change the regular expression for the symbol WORD in the grammar file “poetry.ebnf” as just described. Now both the tests and the compilation of the file “macbeth.dsl” should run through smoothly.

Caution

Depending on the purpose of your DSL, the simple solution of allowing apostrophes within words, might not be what you want. After all “Life’s” is but a shorthand for the two word phrase “Life is”. Now, whatever alternative solution now comes to your mind, be aware that there are also cases like Irish names, say “O’Dolan” where the apostrophe is actually a part of a word and cases like “don’t” which, if expanded, would be two words not separated at the position of the apostrophe.

We leave that as an exercise, first to figure out, what different cases for the use of apostrophes in the middle of a word exist. Secondly, to make a reasonable decision which of these should be treated as a single and which as separate words and, finally, if possible, to write a grammar that provides for these cases. These steps are quite typical for the kind of challenges that occur during the design of a DSL for a Digital-Humanities-Project.

Controlling abstract-syntax-tree generation¶

Compiling the example “macbeth.dsl” with the command python poetryParser.py

macbeth.dsl, you might find yourself not being able to avoid the impression

that the output is rather verbose. Just looking at the beginning of the

output, we find:

<document>

<sentence>

<part>

<WORD>

<ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>Life's</ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>

<ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__> </ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__>

</WORD>

<WORD>

<ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>but</ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>

<ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__> </ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__>

</WORD>

...

You might notice that the output is fairly verbose. Why, for example, do we need the information that “Life’s” has been captured by a regular expression parser? Wouldn’t it suffice to know that the word captured is “Life’s”? And is the whitespace really needed at all? If the words in a sequence are separated by definition by whitespace, then it would suffice to have the word without whitespace in our tree, and to add whitespace only later when transforming the tree into some kind of output format. (On the other hand, it might be convenient to have it in the tree never the less…)

The answer to these questions is that what our compilation script yields is the concrete syntax tree of the parsed text. The concrete syntax tree captures every minute syntactic detail described in the grammar and found in the text. we have to transform it into an abstract syntax tree first, which is called thus because it abstracts from all details that deem us irrelevant. Now, which details we consider as irrelevant is almost entirely up to ourselves. And we should think carefully about what features must be included in the abstract syntax tree, because the abstract syntax tree more or less reflects the data model (or is at most one step away from it) with which we want to capture our material.

For the sake of our example, let’s assume that we are not interested in whitespace and that we want to get rid of all uninformative nodes, i.e. nodes that merely demarcate syntactic structures but not semantic entities.

DHParser supports the transformation of the concrete syntax tree (CST) into the abstract syntax tree (AST) with a simple technology that (in theory) allows to specify the necessary transformations in an almost declarative fashion: You simply fill in a Python-dictionary of tag-names with transformation operators. Technically, these operators are simply Python-functions. DHParser comes with a rich set of predefined operators. Should these not suffice, you can easily write your own. How does this look like?

poetry_AST_transformation_table = {

"<": flatten,

"document": [],

"sentence": [],

"part": [],

"WORD": [],

"EOF": [],

"*": replace_by_single_child

}

You’ll find this table in the script poetryParser.py, which is also the

place where you edit the table, because then it is automatically used when

compiling your DSL-sources. Now, AST-Transformation works as follows: The whole

tree is scanned, starting at the deepest level and applying the specified

operators and then working its way upward. This means that the operators

specified for “WORD”-nodes will be applied before the operators of “part”-nodes

and “sentence”-nodes. This has the advantage that when a particular node is

reached the transformations for its descendant nodes have already been applied.

As you can see, the transformation-table contains an entry for every

known parser, i.e. “document”, “sentence”, “part”, “WORD”, “EOF”. (If

any of these are missing in the table of your poetryParser.py, add

them now!) In the template you’ll also find transformations for the

anonymous parser “:Token” as well as some curious entries such as “*”

and “<”. The latter are considered to be “jokers”. The transformations

related to the “<”-sign will be applied on any node, before any other

transformation is applied. In this case, all empty nodes will be removed

first (transformation: remove_empty). Similarly, the “>” can be used

for transformations that are to applied after any other transformation.

The “*”-joker contains a list of transformations that will be applied to

all those tags that have not been entered explicitly into the

transformation table. For example, if the transformation reaches a node

with the tag-name “:ZeroOrMore” (i.e. an anonymous node that has been

generated by the parser “:ZeroOrMore”), the “*”-joker-operators will be

applied. In this case it is just one transformation, namely,

replace_by_single_child which replaces a node that has but one child

by its child. In contrast, the transformation reduce_single_child

eliminates a single child node by attaching the child’s children or

content directly to the parent node. We’ll see what this means and how

this works, briefly.

Caution

Once the compiler-script “xxxxParser.py” has been generated, the only part that is changed after editing and extending the grammar is the parser-part of this script (i.e. the class derived from class Grammar), because this part is completely auto-generated and can therefore be overwritten safely. The other parts of that script, including the AST-transformation-dictionary, are never changed once they have been generated, because they need to be filled in by hand by the designer of the DSL and the hand-made changes should not be overwritten. However, this means, if you add symbols to your grammar later, you will not find them as keys in the AST-transformation-table, but you’ll have to add them yourself.

The comments in the compiler-script clearly indicate which parts can be edited by hand safely, i.e. without running the risk of being overwritten, and which cannot.

We can either specify no operator (empty list), a single operator or a list of operators for transforming a node. There is a difference between specifying an empty list for a particular tag-name or leaving out a tag-name completely. In the latter case the “*”-joker is applied, in place of the missing list of operators. In the former case only the “<” and “>”-jokers are applied. If a list of operators is specified, these operators will be applied in sequence one after the other. We also call the list of operators the transformation for a particular tag.

Because the AST-transformation works through the table from the inside to the outside, it is reasonable to do the same when designing the AST-transformations, to proceed in the same order. The innermost nodes that concern us are the nodes captured by the <WORD>-parser, or simply, <WORD>-nodes. As we can see, these nodes usually contain a <:RegExp>-node and a <:Whitespace>-node. As the “WORD” parser is defined as a simple regular expression which is followed by optional whitespace in our grammar, we know that this must always be the case, although the whitespace may occasionally be empty. Thus, we can eliminate the uninformative child nodes by removing whitespace first and the reducing the single left over child node. The respective line in the AST-transformation-table in the compiler-script should be changed as follows:

"WORD": [remove_whitespace, reduce_single_child],

Running the “poetryParser.py”-script on “macbeth.dsl” again, yields:

<document>

<sentence>

<part>

<WORD>

<ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>Life's</ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>

<ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__> </ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__>

</WORD>

<WORD>

<ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>but</ANONYMOUS_RegExp__>

<ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__> </ANONYMOUS_Whitespace__>

</WORD>

...

It starts to become more readable and concise. The same trick can of course

be done with the Whitespace inside the part- and sentence-nodes,

only here it does not make sense to reduce a single child:

"part": [remove_whitespace],

"sentence": [remove_whitespace],

Now that everything is set, let’s have a look at the result:

document>

<sentence>

<part>

<WORD>Life's</WORD>

<WORD>but</WORD>

<WORD>a</WORD>

<WORD>walking</WORD>

<WORD>shadow</WORD>

</part>

<ANONYMOUS_Text__>,</ANONYMOUS_Text__>

<part>

<WORD>a</WORD>

<WORD>poor</WORD>

<WORD>player</WORD>

...

That is much better. There is but one slight blemish in the output:

While all nodes left a named nodes, i.e. nodes associated with a named

parser, there are a few anonymous <ANONYMOUS_Text__>-nodes. Here is

a little exercise: Do away with those <ANONYMOUS_Text__>-nodes by

replacing them by something semantically more meaningful. Hint: Add a

new symbol “delimiter” in the grammar definition “poetry.ebnf”. (An

alternative strategy to extending the grammar would be to use the

replace_parser operator. In the AST-transformation-table ANONYMOUS

nodes are indicated by a leading ‘:’, thus ins the

AST-transformation-table you have to write :Text instead pf

ANONYMOUS_Text__ which is merely the XML-compatible name.)

From here onward¶

Congratulations, you have finished the step-by-step-guide for creating a domain-specific language! To get deeper into the matter and, in particular, to master the art of grammar writing, it is best to start your own pet-project.

If you do not feel confident enough yet or if you run into trouble, I recommend that you read the manual on DHParser’s :ref:` testing framework<testing>`, first, because it takes you on a tour through another, less trivial, step-by-step example explaining in detail testing-strategies and the testing framework along the way. Unit-Testing helps tremendously when writing grammars, especially if you are a beginner.

You might then want to look into the other manuals, each of covers a different stage in the processing of a DSL-file from its source-code to the desired destination format. Enjoy the ride!